Aldous Huxley

(via Laura Huxley)

By Steve Penhollow

The Journal Gazette, Fort Wayne, Indiana.

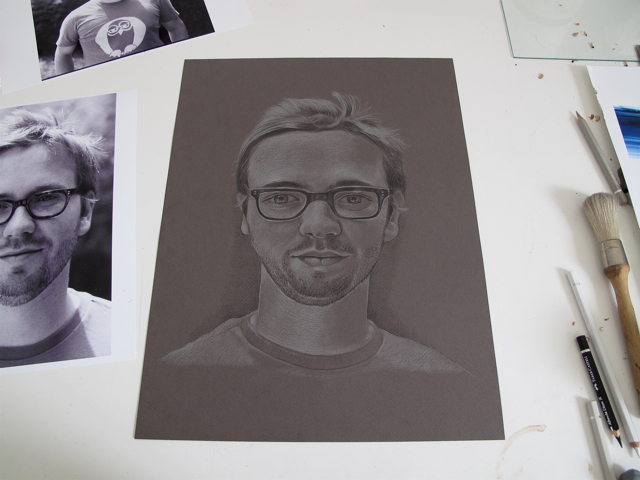

Peter Stichbury, a New Zealand artist, painted a portrait of Zach Klein based on an Internet photo. A photo of Fort Wayne native Zach Klein online inspired a New Zealand artist to paint this portrait of him. And a strange story branches off from there …

Serendipity strikes different people different ways.

Some people think it’s merely amusing. Others see something spiritual in it.

Serendipity, which I take to mean extraordinary, advantageous coincidence, can brighten up your day or add meaning to your life, depending on who you are.

What follows is a story of serendipity that seems serendipitously designed for Fort Wayne residents.

It starts with Zach Klein, the Bishop Luers High School grad who moved to New York, co-founded the Web sites CollegeHumor, Busted Tees and Vimeo, and then sold them all to Barry Diller’s InterActiveCorp in 2006.

In January 2008, Klein received an unsolicited e-mail from Peter Stichbury, a New Zealand artist unknown to him. Stichbury had run across a photo of Klein on a Web site and asked for permission to paint a portrait based on the image.

“It was unusual, but I was flattered by the request,” Klein wrote in an e-mail.

Permission was granted, and Stichbury went ahead with his portrait, a little piece of a larger whole.

Stichbury said his work these days is “immersed in cyberspace identity.”

“To me, it was fascinating how the entrepreneurial Mr. Klein had constructed such an extremely elaborate and detailed Internet persona using sites like Vimeo, Tumblr and Flickr, etc.,” he said in an e-mail.

As near as I can figure, Stichbury’s portraits are attempts to artistically render not just single images, but the comprehensive if convoluted way people represent themselves on the Web.

A year after Stichbury first contacted Klein, the finished work was exhibited in a giant art show at the Los Angeles Convention Center called ART LA.

It was there that Kate Keller, a Santa Monica, Calif.-based textile designer, fell instantaneously in love with Stichbury’s portrait of Klein.

“My friend rolled her eyes at me,” Keller said by phone. “I guess it takes a certain aesthetic sense to appreciate it.

“But my (life) partner came over and said, ‘I want to show you something,’ and she led me to that same piece,” she said.

Keller and her partner put a hold on the piece even though two people had already done so.

Which is to say, if Keller was going to own the piece, she’d need the other two candidates to bow out.

“I couldn’t stop thinking about it,” she said about her mind-set in the ensuing days of waiting. “I did some research on the artist on the Internet and came across Zach’s home page and Flickr page. The Flickr page had the painting on it.”

The effect of the painting on Keller was ineffable and inexpressible, two words that might describe the effect of all paintings on the people who love them.

“The piece was nostalgic in a way,” she said. “It felt sort of comfortable.”

Eventually, the L.A. gallery owner did call and offer them the piece.

Here’s where things got a little weird.

Keller had been corresponding with Klein by e-mail, and eventually the subject of Klein’s hometown came up. Keller was startled to discover that Klein, with whom she had never corresponded before seeing his portrait, was from Fort Wayne.

She was startled because that’s where she’s from, too.

Keller is a graduate of Homestead High School.

And on the same day that Keller visited the exhibit, Klein had also flown in for a peek. They determined they’d missed each other by mere minutes.

Two people living on opposite coasts of this country find common ground and uncommon congruence thanks to the artistic efforts of a man living in New Zealand.

Sure sounds serendipitous, however you define it.

Keller defines it as more than merely entertaining.

“It happens to me all the time,” she said. “Some people are really in tune. I don’t know. I am very sensitive. It’s not something I can explain.”

Klein also sees consequence in coincidence.

“Serendipity to me is the manifestation of synchronicity,” he wrote. “We’ve all made and will continue to make a tremendous number of decisions that ultimately put us in proximity with other people who’ve made a similar set of choices. I believe that most events in the world aren’t random at all, they’re likely. Still, despite knowing this and believing it to be a factor, I’m completely astounded by the case of Kate buying my portrait.”

Philip Glass for Sesame Street - Geometry of Circles, MuppetWiki

Jackie Kennedy Onassis painting with daughter Caroline.

September 13, 1960

Photo: Alfred Eisenstaedt

(via life)

Paul Winchell, April Winchell and Jerry Mahoney.

September 1952

Photo: Gordon Parks

(via life)

We are all voyeurs in beauty’s collective dream.

They might be portraits of the newest stakeholders in the fame game: downtown lounge lizards, uptown debutantes and about-to-be-discovered supermodels. Some look snap-frozen, as twinkly as popsicles: twenty-somethings possessing potent, engaging eyes and projecting intriguing auras, mystifying personas. Others look barely post-adolescent and seem still dewy, as if freshly emerged from cocoons, self-consciously stretching glittery wings.

Glamour, like a transparent shield or bubble, encases them; each is a wise child, ready for the close-up, the adoration of a camera lens. You imagine them – girls and boys, the young and the restless, these gilded youths – as speaking with sugary automated voices slightly out of synch with the movement of their luscious bee-stung lips, their android-smooth skins.

These living dolls are, in fact, paintings concocted by Auckland artist Peter Stichbury, whose aim is to reveal beauty as a collective dream in which we are all secret voyeuristic sharers.

The portraits – 30 individual studies, most in acrylics on stretched linen but some painted onto small wooden spheres – have been gathered together by curator Emma Bugden for Stichbury’s travelling exhibition The Alumni.

Yet if Stichbury is a portraitist, a society- painter, his subjects, despite their solid delineation, can be elusive; they are changelings and composites. With their semi-allegorical names, near-flawless complexions and hyper-real sheen, they are emblems as much as real people. Generic specimens and types, they represent our over-mediated world with its focus groups and database assumptions, where every singularity is framed, screened and catalogued. Stichbury offers a crowd of lookalikes and stand-ins, all with mesmerising appearances.

There are some instantly recognisable people, such as local pop musician Dudley Benson and movie star Anna Paquin. But Stichbury is not after instant recognition; rather the wound-up, intense faces he offers provoke a double take. The euphoniously named Anna Paquin (2004), for example, an actor at once grounded and aware of the power of stardom, gazes at us with gigantic insectoid eyes, her eyelashes jutting like predatory spider legs. Though her long, dark-brown hair is tucked behind her ears, the rococo S-curve of one strand hangs free, echoing the great curved dome shape of her forehead. Pushing and pulling at the contours of Paquin’s face, Stichbury has given her cartoonish features and transformed her into a kind of alien, who holds us, as if paralysed, with the power of her gaze.

There’s more than a bright, intent look on Paquin’s face; there’s a burning radiance, as if the artist’s careful applications of layer after layer of colours blended together to give weight and depth and presence are actually an ironic meditation on the artificial, the fake, the unreal.

Exaggerating feminine allure, another portrait, Glister (2004), gives a girl’s lit-up febrile face the fragile brittleness of blown glass; while Juvenile (2000) inserts eyeballs that bulge like heavy lustrous globes in a classic, oval-shaped face. Examine Juvenile’s pupils, and you see that they are extremely dilated, as if she’s in the grip of some chemical enhancement, some practical lesson in biochemistry perhaps.

Stichbury first came to wide public notice when he received the James Wallace Paramount Art Award in 1997, while still a student at Elam School of Fine Arts. His award-winning painting, Truce (1997), part of a series about Germany’s Weimar Republic and inspired by Weimar social satirists such as Max Beckmann and Otto Dix, explored male friendships and relationships in a distinctive way, and his interest in male psychology, in male role-playing, remains central in The Alumni.

It is not stereotypical macho behaviour under his magnifying glass, however, but rather the complex ambivalence of free-floating emotions, as in his portrait of Eddie Vaughan (2004), sourced, we are told, from the internet as a police mugshot, which the artist has then manipulated. Vaughan, looking both baffled and angry, glares out at us. His face, with again the exaggerated, big domed forehead, is not only a blotchy pink, but also covered with a pattern of fine scratches, as if he’s been dragged facedown through bushes or across gravel. Alongside this painting is a portrait of one Joe Gruver (2007), nursing a black eye the same shade of mauve as his shirt.

Expressions blend and morph in The Alumni, as if feelings are not just being registered by individuals, but also flickering and being transmitted from portrait to portrait. There’s a spectrum covered, too, from shock and awe to yearning and gloating. Ultimately, each face, displayed like a boutique item, is bittersweet, as if the possibility of deflation is lurking behind the inflated self-esteem.

Stichbury is on about the modern comedy of manners, where private diaries are on blogs and Facebook, and where social anxiety consists of not being connected, always available. This is an age attention is measured in blink rates, the digital has destabilised a sense of permanence and idealism has been appropriated by fashion.

If commodification is the gold standard, fracturing and fragmentation of identity might loom for us all. Teasing and coaxing out elements of personality, Stichbury offers the portrait as a performance, but in studying the theatrical mask of the face, he also makes it transparent, and poignant.

Peter Stichbury: The Alumni, Dunedin Public Art Gallery

by David Eggleton

(courtesy The Listener)

little girl loves aphex twin

Boards of Canada

Everything you do is a balloon

Zach/Zach

What we know about individuals, no matter how rich the details, will never give us the ability to predict how they will behave as a system. Once individuals link together they become something different … Relationships change us, reveal us, evoke more from us. Only when we join with others do our gifts become visible, even to ourselves.

Wheatley

“Be a good boy, remember; and be kind to animals and birds, and read all you can.”

Shetland Islands

(photo K. Martin)

tlvx:

“Poe’s Law relates to fundamentalism, and the difficulty of identifying actual parodies of it. It suggests that, in general, it is hard to tell fake fundamentalism from the real thing, since they both sound equally ridiculous. The law also works in reverse: real fundamentalism can also be indistinguishable from parody fundamentalism.

“For it is not possible to step twice into the same river, according to Heraclitus, nor to touch mortal substance twice in any condition: by the swiftness and speed of its change, it scatters and collects itself again-or rather, it is not again and later but simultaneously that comes together and departs, approaches and retires.”

“What is a House?” by Charles Eames. Published in the July 1944 issue of Arts & Architecture.