Old Smelly Haircut

Blizzard

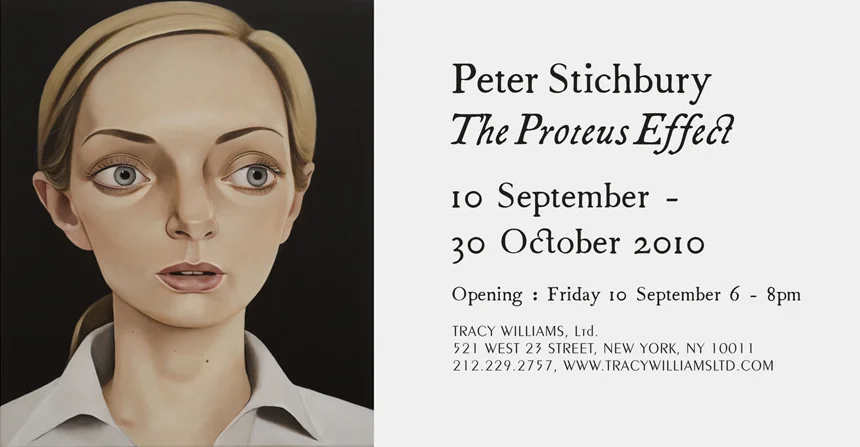

Peter Stichbury The Proteus Effect

by Genevieve Allison

In Peter Stichbury’s first solo show at Tracy Williams, The Proteus Effect, the artist’s characteristically pristine paintings and prints of typal plastic looking faces line the walls, often reproducing the same figure in several identical works. His painterly style, if you’re not familiar with it, is characterized by a smooth, highly finished acrylic rendering that is naturalistic yet unrealistic. Nacreous, like polished pebbles, the uniqueness of each feature is either distended or obliterated by the artist’s exaggerated stylisation.

At first glance the impeccable mimicry of these reproductions comes across as a rather banal exercise of painterly virtuosity. Each detail of the canvas is perfectly blended and painfully precise. In fact it is the boredom with this perfection that invites the viewer to do primitive things like try and spot the differences … and discover the conceptual underpinning of the series. On closer inspection, or rather after prolonged staring, the carbon copy images reveal themselves not to be carbon copies. From image to image, the proportions between identical faces have been subtly, almost imperceptibly tweaked.

These small changes, once noticed, do seem to affect the aesthetic reception of each face. Just by a slight re-proportioning, Bernard M somehow becomes less adolescent than Bernard 1 or Bernard 2; Estelle, in her six different renditions, morphs ever so slightly between the elfish, porcine and womanly as her eyes shift in size and relation to her forehead, chin and nose.

It is almost impossible to talk about human form and the ratios understood to generate feelings of aesthetic harmony without reference to classical ideals. While the location of beauty is a very imprecise science according to more contemporaneous and therefore plural attitudes, these images seek to illustrate the subtle volatility of facial enigma, and therefore reverberate with platonic principles. With one exaggerated ratio the appeal or impression of a face can alter. This must be, in part, the Proteus effect. In Greek mythology Proteus is a primordial sea-god endowed with the ability to morph form, ‘the protean’ denoting to the mutability of self-representation.

As Proteus can voluntarily change form, so too can the average modern human by way of the profile-creating machinery of social media networks. The portrait of Mark Zuckerberg, the founding creator of Facebook, indicates this concern a little too literally. Although the world is generally much more aware of whom Zuckerberg is, now that the movie The Social Network is out and the identity behind Facebook has been subject to greater attention, for the last several years he has been the unseen face behind a seemingly acephalous virtual empire. He is, like many of Stichbury’s subjects, a little geeky and awkward. Though what is far more interesting (than his face) is the explicit breed of ‘image-making’ that is endemic to the form of self-representation he created.

Stichbury’s images, like social network profiles, are half construct, half reality - a synthesis of images from newspaper clippings, the internet and his own imagination. They present (or evoke) stereotypes, ideals and felicities. Many of the features he depicts are appropriated from people he has never met. In some respects the relationship here between painter and subject reverberates with the co-existent familiarity and alienation that occurs with interconnectivity. These portraits do not resonate with the enigma or presence of reflective human beings; they are not Sprengler’s “biography in the kernel” (F. David Martin, “On Portraiture”, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol.20 No.1 [Autumn 1961] pp.61).

Rather, they are surfaces that depict a vacant, inaccessible self-consciousness. The type we find mannered in advertising and popular media. Far from the intimate urban encounters and humanism of 19th and 20th century portraiture, these paintings are less involved with generating a sense of an individual’s character or presence than of discussing an alternate space where inter-human relations appear to have been dis/misplaced.

These reflections are timely, but come across hedged with anti-futurist paranoia due to their pairing with classical mythology. The suturing of classical narratives, conventional portraiture painting and thematic concerns relating to digital media, suggests a proleptic regression. In the west, the history of portraiture extends back to antiquity but it wasn’t until the Renaissance, after centuries where generic and stylised forms of representation had been the norm that distinctive likeness began to reappear. The change reflected a growing interest in everyday life as well as individuality and notions of identity. Now we file the same format, confronting and embracing ubiquity and genericism.

If portraiture “seeks to bring out whatever the sitter has in common with the rest of humanity” (quoted in Shearer West, Portraiture [Oxford, 2004], p. 24), Peter Stichbury is doing exactly that. At the time of writing this, there are over 500 million currently active members of Facebook.

Genevieve Allison

Eyecontact, 9 December, 2010

Photos: http://eyecontactsite.com/2010/12/stichbury-in-nyc#ixzz17bGlHC6G

Helen Newington Wills Roark

1928

Haig Patigian

Gould’s Chair

Gould was renowned for his peculiar body movements while playing and for his insistence on absolute control over every aspect of his playing environment. The temperature of the recording studio had to be exactly regulated. He invariably insisted that it be extremely warm. According to Friedrich, the air conditioning engineer had to work just as hard as the recording engineers. The piano had to be set at a certain height and would be raised on wooden blocks if necessary. A small rug would sometimes be required for his feet underneath the piano. He had to sit fourteen inches above the floor and would only play concerts while sitting on the old chair his father had made. He continued to use this chair even when the seat was completely worn through. (via)

(image: Barbara Bloom, Lüttgenmeijer, Berlin)

“Learn the principle, abide by the principle, and dissolve the principle. In short, enter a mold without being caged in it. Obey the principle without being bound by it. ”

“The dilemma I faced in New Guinea was this: I had been asked to find more effective uses for electronic media, yet I viewed these media with distrust. I had been employed by government administrators who, however well-intentioned, sought to use these media for human control. They viewed media as neutral tools & they viewed themselves as men who could be trusted to use them humanely. I saw the problem otherwise. …. I think media are so powerful they swallow cultures. I think of them as invisible environments which surround & destroy old environments. Sensitivity to problems of culture conflict & conquest becomes meaningless here, for media play no favorites: they conquer all cultures. One may pretend that media preserve & present the old by recording it on film & tape, but that is mere distraction, a sleight-of-hand possible when people keep their eyes focused on content. …. I felt like an environmentalist hired to discover more effective uses of DDT.”

Edmund Carpenter

(via M.Wesch)

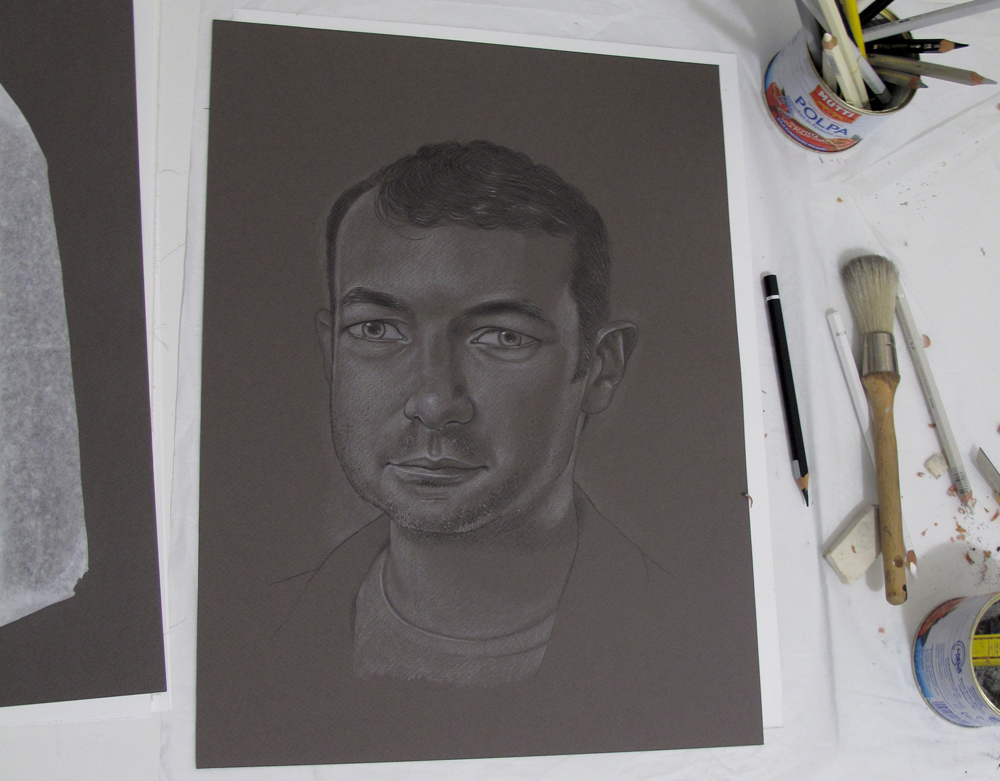

*Image Estelle study, 2010

Jean-Baptiste Greuze A Young Peasant Boy, ca.1763

oil on canvas

18 7/8 x 15 3/8 inches (47.9 x 39.1 cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Zach Klein in avatar

(thanks zk)

Tracy Williams Ltd. is pleased to announce Peter Stichbury’s first solo exhibition at the gallery and the Auckland-based artist’s first solo exhibition in North America. In The Proteus Effect, Stichbury presents five paintings and a suite of prints which reflect the metamorphosis that occurs through digital self-representation via the use of avatars and invented personas. Stichbury’s subjects possess an unearthly, distorted countenance—their visages are devoid of life and instead exude a chilling sterility and distance that echoes the airbrushed simulation and uncanny perfection prized in postmodern conceptions of beauty. These portraits do not depict individuals, rather archetypal personas; his subjects are culled from contemporary media and pop-cultural imagery, spanning vernacular sources such as glossy fashion magazines, advertising campaigns, yearbooks and online fashion model go-sees. Consequently, the overarching flatness and superficial patina seem to defy traditional notions of portraiture, as they do not embody a sense of expressiveness, character or emotional valence. Rather, these highly-stylized portraits represent anthropomorphic façades that are as much elusive enigmas, ones that mirror the very fabrication that occurs when creating an idealized virtual identity within such social environments like Facebook, Second Life, and Chat Roulette. Like the Greco-Roman sea-god Proteus, known for his ever-shifting, mutable form, Stichbury has chosen subjects that function as magnified, real world avatars, constantly morphing to increase status, affiliation, event or social cause. Such portraits of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and Vimeo designer Zach Klein, elicit larger questions surrounding the role authenticity and interpretation as manifest in both authentic and virtual worlds. They encourage us to ask: how do these crafted personas and our own behavior intersect and reflexively inform each other in the ‘real’ world? What are the consequences of such a correlation between virtual physiognomy, everyday comportment and its role in influencing societal notions of beauty? Above all, how is each of us implicated in the way we craft our own personal avatars or personas through such tools of social mediation?

I fulfilled a dream and bought some land Upstate. I call it “Beaver Brook” for the Delaware tributary that runs through it. I took possession of it yesterday and Noah came up with us to explore the property together. There are a few cabins dotted throughout and the three of us slept in the main cabin shown above.

Zach and Courtney, Beaver Brook.

(thanks MB)

Alexander Pope

The Trumpeter Swan

1900